In the 19th century, railroads played a revolutionary role in the United States. It helped foster a unified market across the vast North American soil, spawned the steel revolution in the new world, and triggered numerous business management and financial innovations.

The construction of American railroads in the 19th century relied on market forces, financed by debt and equity securities. Initially, equity was the preferred tool, but since the 1850s, mortgage bonds started to dominate the financing due to the ever-increasing amount of funds required. Eventually, defaults spread through the industry as huge interest expenses overwhelmed operating profits in business and financial cycles. In the late 19th century, nearly one-fifth of the railway mileage in the US suffered from defaults and was put under receivership. The railway network was at risk of being liquidated and dismantled.

Solving defaults are no easy job at that time. Congress had repealed all three bankruptcy acts, and the government had little to help given no authorization from the legislative authority. The judicial system was to the rescue, making a series of precedents based on the principle of “public interest, rather than debt-holder interests, first.” Efforts of the judicial system pushed forward debt restructure and helped remake the US railway industry.

Given the de facto judicial legislation, the private sector protected its interests by financial innovation. Instruments such as deferred interest debts and preferred stocks became widely applied while voting trusts were formed. Together they helped reduce the fixed interest payments of railway companies and enhance external supervision of managers, improving the efficiency of railway operations and management.

The above history sheds light on infrastructure investment in today’s world. Efficient infrastructure construction can not only stimulate short-term economic growth but can also catalyze the fundamental transformation of an economy. However, utilizing infrastructure as a transcending force requires high investment accompanied by high risks. Efficient and adequate investment is beyond the capability of the public sector alone, but private participation in the form of mounting debt is unsustainable.

A collaboration between the visible and the invisible hand can help foster sustainable infrastructure financing. Public agencies should always be committed to acting according to public interests by setting up rules for the game. This will offer the stage for private stakeholders to interact and smartly divide risks, benefits, and costs among themselves through financial and institutional innovation.

Railroad: America’s first big business

Railroads in the 19th century played a revolutionary role in the industrialization of the United States. Alfred Chandler, an American scholar called “the doyen of American business historian” named his book on the US railroad research as “Railroads: The Nation’s First Big Business” to highlight that railroad is the first modern industry in the American continent.** 1 2 In fact, in 1890, a time when the steel and textile induries also became highly developed, the market capitalization of railroad stocks still accounted for 75% of the total market capitalization of the U.S. stock market, down from 86% in 1880 and 92% in 1870.**3

Chandler summarized three aspect of transformation brought by the railway system. First, railroads accelerated the formation of a unified market by reducing the time and costs of land transportaion of goods and people by an unprecedented scale. For example, the travel time from New York to Chicago was cut from three weeks to three days and would not be affected by the fronzen rivers and storms any more. Together with telegraphs and steamships, new modes of transportation made it economical and profitable to send agricultural products and coal from the hinterland to the eastern coastal areas at lower prices. Business flourished, while rail hub cities such as Chicago prospered.

Second, railroads induced industrialization by stimulating the development of the steel industry. In early 19th century, iron in the US was mainly produced by blacksmith workshops. Limited demand made it unprofitable to invest in large-scale coal-based smelting technology developed in Europe. Mass construction of railroads in the second half of the 19th century completely changed the picture as demand for iron increased rapidly, stimulating the set up of iron factories. Meanwhile, to increase the life of the tracks, methods were explored to make iron more resistent, leading to the perfection of steel making process. By 1880, three-quarters of US steel production had been consumed for the manufacuturing of rail tracks and locomotives. The steel business eventually attracted brilliant entrepreneurs, such as Carnegie, who reduced the costs of steel production with technological and management innovations, spreading the first industralization in the US continent. 4

Third, railroads sparked a management revolution. Compared with the agricultural and textile industries at that time, railway construction and operation were much more complex. Chandler documented in a 1965 paper that the Penssylvania Railroad had nearly 50,000 employees in 1880, while textile enterprises at the time rarely employed more than 2,000 people. [^5] At the same time, the railway operates across a large geographical scope, consist of different sections, such as stations, warehouses, and bridges, and efficient management requires timely decision making from time to time. All these new characteristics led to the development of new management practices tailored to modern complex enterprises, such as professional managers, hierarchical systems, and workers’ unions. Meanwhile, financial innovation also emerged to fulfill the huge amount of money required for railroad construction, which is discussed in the next section.

Financing US railroad investment in the 19th century: from equity to debt, followed by defaults

Before the 1850s, equity issuance dominated railroad financing. On the one hand, the railway lines constructed in this early period were shorter and thus required less investment. On the other hand, these lines represented the busiest transportation routes, guaranteeing nice profits, and thus annual fixed interests were too little compensation compared with equity gains for investors. 5

However, golden investment opportunities with low costs and high returns had gradually faded over the years. New investments started to require an ever-increasing amount of money. According to Chandler’s research, from 1850 to 1855, at least 10 railroad projects were capitalized with more than $10 million, with five of them above $19 million. Textile factories at that time serve as a good comparison. The largest textile factory at that time required an initial investment of $500,000, while by 1850 there were only 41 textile mills built with an investment of $250,000 and above. Railroad investment also paled canals. For instance, the Erie and Champlain Canals cost only $7.5 million. [^7]

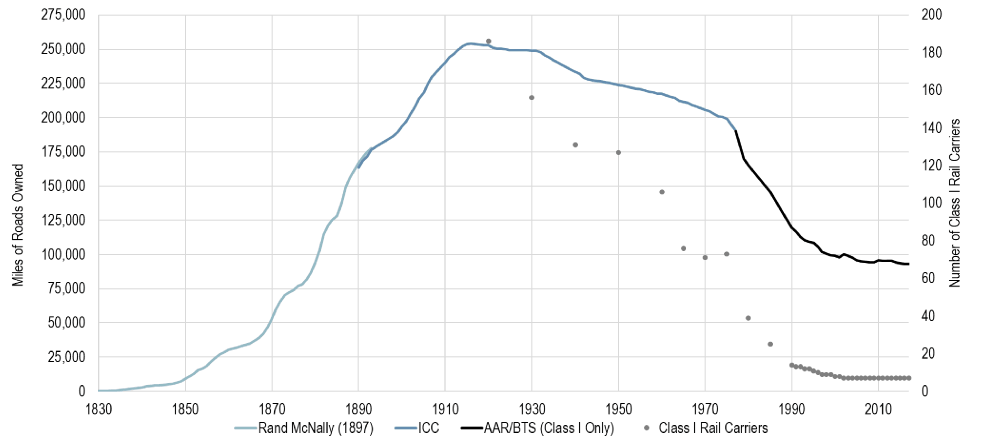

The amount of railway investment was considerable from a macroeconomic perspective. According to Tufano (1997), stocks and bonds issued by US railroad companies totaled $2.72 billion from 1880 to 1884. 6 According to Gallman (2020), the US Gross National Product (GNP) excluding inventory adjustment and Gross Fixed Capital Investment (GFCI) over the same period were $56 billion and $10.73 billion, respectively. 7 A simple calculation shows that funding raised by railroad companies amounted to 4.8% of GNP and 25.3% of GFCI during those five years. Those were the golden years of the US railroad development, with railroad mileage increasing from 55,000 miles in 1870 to nearly 200,000 miles in 1900 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The US Railroad Mileage and Class Rail Mileage: 1830-2017

Obtained from The Geography of Transport System link. “)

Figure 1 The US Railroad Mileage and Class Rail Mileage: 1830-2017

Obtained from The Geography of Transport System link. “)

Increasing investment needs and higher uncertainty on profits made debt financing more attractive, which had gradually surpassed equity issuance in the second half of the 19th century. Tufano’s statistics show that the ratio between equity and bond issuance for the US railroad companies rose from 1:0.62 in 1875-1879 to 1:1.58 in 1885-1889. Most of the bonds are collateralized by railway fixed assets, such as track sections, with an annual interest rate of about 7%, maturing in 20 to 30 years. For investors, mortgage bonds were secured senior debt claims. In case of defaults, foreclosures help bondholders minimize loss by operating or liquidating the underlying assets 8

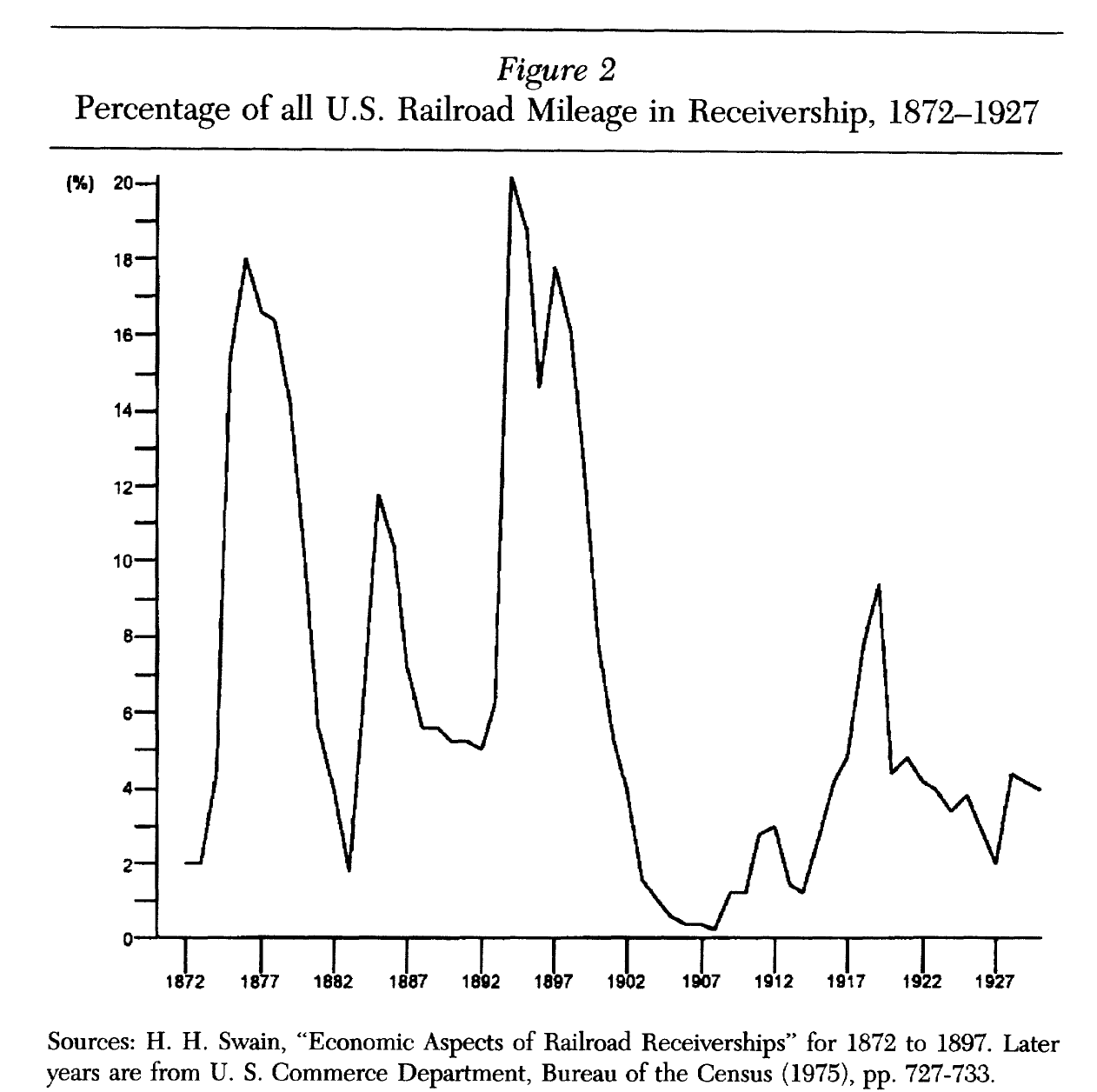

A 7% interest rate is not high for some developing economies today. For instance, to contain rising inflation, Brazilian and Russian central banks have been hiking policy rates since 2021, which have reached 9.5% and 10.75% in February 2022, respectively. However, when the associated principal is large enough, a 7% coupon translates into fixed interest expenses high enough to choke a company. Indeed, after the 1870s, railway price wars and macroeconomic downturns led to declining revenues, which in turn caused a wave of railway bond defaults. According to Tufano’s research, by the end of the 19th century, about one-fifth of mileages were under receivership due to defaults (Figure 2). Supporting this view, Levy (2022) argues that at least one-third of U.S. railroad companies fall bankrupt in the 1890s.

Figure 2 Percentage of U.S. Rail Mileage in Receivership: 1872-1927

Cited from Tufano (1997).

Figure 2 Percentage of U.S. Rail Mileage in Receivership: 1872-1927

Cited from Tufano (1997).

Debt Overhang

Two options serve as a solution to mortgage debt defaults: restructure or foreclosure. In the case of railroad companies, foreclosures were difficult due to network effects. That is, when sections of railways are each passed to different groups of bondholders, railway operations will have an even lower efficiency. Investors probably will choose to liquidate fixed assets through firesales to cover losses. Either way, the enforcement of mortgage rights will drag, if not reverse, the US railroad development.

These leave restructure as a more reasonable solution. However, as is told by economic theories, debt restructure is an extremely complex game, involving existing equity holders, existing debt holders, the management team, external equity investors, and external debt investors. Allocating rights, benefits, costs, and risks across diverse stakeholders is no easy job.

Meanwhile, for railroad companies, debt restructure is more difficult because stakeholders need to reach agreements not only on the reduction of existing debts but also on how to finance the considerable additional working capital to advance wages, purchase equipment, replace broken rail tracks to get the business running. And this is a huge amount of money. According to Chandler, the operating costs for the Western Railroad in 1859 was $608,000, $2.86 million for the Erie Railroad in 1855, and $5.43 million for the Pennsylvania Railroad 1869. For comparison, Pepperell Manufacturing Company, one of the largest textile companies in the United States in the 19th century, had an operating cost of $300,000 in 1850. 9

The need for new funding creates a more complex Debt Overhang problem. Existing investors, who are eager to limit losses, usually try their best to spend no more dollars, but inviting new investors is associated with conflicts on the allocation of risks and responsibilities. Mortgage bonds are senior claims, and the same underlying assets usually are prohibited from securing new bonds. Without collaterals, newly issued bonds are considered junior to secured mortgages, which will be paid first in the future. This puts potential investors off as they pay more while receiving little.

Institutional uncertainties introduced by the absence of bankruptcy legislation made restructuring even harder. The U.S. Congress passed the Bankruptcy Act in 1800, which was repealed 3 years later. A new Bankruptcy Law was passed in 1841 but was repealed again in eight months. After the Civil War, Congress passed a third bankruptcy law in 1867, but it was repealed again in 1878. Meanwhile, all three acts dealt with the bankruptcies of merchants and individuals, offering little insight into solving the bankruptcies of complex corporations. 10 Given this, it is impossible to count on the legislative or the executive branches to help solve defaults.

The Judicial System to the Rescue

Finally, it was the judicial branch that acted as the visible hand to guide the railroad industry out of debt traps through “judicial legislation” . 11

The judges insisted that railroads are an industry of strategic importance and that safeguarding the public interest should be the first principle of default solution. Gerald Berk, an American political scientist, argues that “Judges’ main consideration in ruling on the railroad bankruptcies was to foster the continued development of the nation’s railroads as a nationally integrated system.” 12 In practice, judges allowed np suspension, liquidation, or dismantling of the railway system that could harm users’ benefits and limited the bargaining power of existing creditors by their rulings.

On the one hand, they redefined the rights of mortgage bondholders. Since they are secured debt claims, mortgage repayment should have been prioritized over unsecured junior debt holders. However, rulings supported that certain unsecured debt claims could be repaid before settling mortgages, such as trade payments to suppliers. Rulings also supported the issuance of Receivers’ Certificates, which were debt raised by managers of defaulted railways (usually railway managers) collateralized by the entire railway line. These are considered “judicially-sanctioned securities” and thus have higher repayment priorities against existing mortgages. Despite several appeals by existing mortgage creditors from 1872 and 1886, arguing these rulings breached the spirit of the contracts, the Supreme Court upheld them in 1886.

On the other hand, judges supported restructuring plans that benefited external new investors, contributing to the settlement of debt overhangs. In essence, two approaches were introduced. The first is the introduction of an “Upset Price”. That was a fixed amount of money paid to investors who voted against an approved restructuring plan. The amount, set by the court, is usually relatively low, encouraging existing investors to vote in favor of the plans. The second is to ask existing equity holders to pay “assessment fees”. They need to invest extra money if they wish to acquire the equity of the restructured company. The collected funds were used to pay for “Upset Price” and partially repay recoveries’ certificates (thus, the existing equity holders indirectly paid the working capital of railway operations).

These efforts accelerated the restructuring process, significantly reducing the principal and interest expenses of railroad companies. According to Tufano (1997), who studied 57 railway companies restructured during 1884-1899, their debt outstanding declined by 22% and interest expenses by 35% after restructuring. The annual average interest rate dropped to 4.72% from 5.78%. Levy (2022) also documented that for railroad companies restructured by JP Morgan and other Wall Street investment bankers, debt was usually cut by a third on average.

Innovations from the private sectors followed these rulings, adjusting railway companies’ capital structures and management approaches. Knowing that the judicial system may hurt their benefits again to protect public interests in case of new defaults, financial investors tried to defend their interests by reducing the probability of default while enhancing external monitoring. Preferred stock, deferred coupon bonds, and covenant bonds became widely used. For instance, certain covenants allowed holders of preferred stocks to nominate managers if dividends were deferred continuously. Voting trusts were also formed to delegate monitoring authority to professionals. These private-sector innovations reduced the financial risks of railroad companies and improved efficiency, and the US railroads have since experienced no major default tides.

Summary

Four insights are drawn from the above history for infrastructure investment today.

First, infrastructure investment, when properly done, can act as a transending force for economic development. For the US economy in the 19th century, railway investments were important not just because it was a public goods that can be used by various economic activities. Rather, the qualitative reduction in transportation costs and time led to qualitative change of how production and consumption was organized. It contributed to the formation of a unified large-scale market, stimulated innovations in finance and management, and accelerated the expansion of the first industrial revolution in the US. Welfare and short-term growth are good reasons for infrastructure investment, but encouraging those transformative changes should also be considered, if not prioritized.

Second, private participation is indispensable in investing for the above-mentioned transformative infrastructure. Powerful and desirable as they are, infrastructure that brings revolutionary effects are usually expensive, complex, and risky. The public sector alone will not be able to mobilize sufficient resources for investment, nor will it able to implement the project efficiently without professional management teams. Meanwhile, excluding the private sector asks all tax payers to equally bear the risks of infrastrucutre investment, instead of allocating those risks across groups of the society propotionally to their ability of risk-taking. Therefore, private participation should be mobilized to the greatest extent in infrastructure development.

Third, private participation through high leverages may not be sustainable. A key feature of infrastructure capital is longevity, whose construction and operation spans across one or more business cycles. Therefore, there is a likely scenario that a project meets economic downturns in its initial years of operation, resulting in low profits or losses. Should that happen, a large amount of fixed interest payment will bring substantial financial risks. From the history of the US railraod development, a 1:1.5 equity-to-debt ratio associated with a 7%-interest are enough to trigger default waves. This serves as a wake-up call for infrastructure investment today, especially to projects in Chinese counties. Better project screening is required, as well as better risk allocation through innovative financial instruments.

Fourth, the visible hand has a role to play in encouraging private collaborations that promote public interests. In settling the railway default wayts, the us judicial system set the for all stakeholders that the public interest should be put to the first place, even prioritized against privte contracts. This serves as a moral fundation for adjusting the bargaining power of existing and new investors. Framed by those “judicial legislation”, private stakeholders interacted each other with innovations to maximize their own benefits. In other words, the public sector upheld a desired object and designed smart mechanisms for the private sector to function, instead of directly dictates what to do or completely avoid interfereing. [15]

Notes and References

[^5:]: Chandler, A. D. 1965. “The Railroads: Pineers in Modern Corporate Management”. The Business History Review. Vol. 39 (1).

Investors during this period were mainly from Boston, but as Boston’s industrial capital was trapped in the crisis of 1840, subsequent financing increasingly shifted to New York investors who had accumulated a lot of money in cross-border trade.

[^7}: See Chandler (1965).

Conceptually, stock and debt financing are not exactly equivalent to the actual investment in railways in the same time period, but can be used as a benchmark.

-

see https://www.economist.com/books-and-arts/2017/08/24/how-technology-and-capitalism-shaped-america-after-the-civil-war ↩

-

Chandler, A. D. 1981. The Railroads: The Nation’s First Big Business. Ayer Co Pub. ↩

-

See Table 1 Degree to which Railroads Dominate within Cowles’ All Stock Index During the 19th Century. McQuarrie, E. 2021. Introducing a New Database of 19th Century Railroads Before Cowles and Macaulay. Working Paper. ↩

-

Levy, J. 2022. “Chapter 8 Industrialization”. Ages of American Capitalism: A History of The United States. Random House Trade. ↩

-

For railway financing before 1850, see Chandler, A.D. 1954, “Patterns of American Railroad Finance: 1830-50”. The Business History Review. Vol. 28(3). ↩

-

Tufano, P. 1997. “Business Failure, Judicial Intervention, and Financial Innovation: Restructuring U.S. Railroads in the Nineteenth Century”. The Business History Review. Vol.71 (1). ↩

-

GNP and fixed capital formation are from Table 5.3 Gallman’s annual national product series, measured in current prices, 1869-1909, in million dollars, Gallman, R.E. and Rhode, P. W. 2020. “Chapter Five Gallman’s Annual Product Series, 1834-1909”. Capital in the Ninteen Century. University of Chicago Press. ↩

-

See Tufano (1997). ↩

-

Chandler (1965). ↩

-

Tufano (1997). ↩

-

This section mainly refers to Tufano (1997). ↩

-

Berk, G. 1994, Alternative Tracks: The Constitution of American Industrial Order, 1865-1917. 47-72, cited from Tufano (1997). ↩