-

Introduction

-

Risk allocation: traditional Public-Private Partnership models shift infrastructure project risks from the government to the private partner.

-

Investment Hold-up: however, the success of infrastructure projects depends on local governments’ efforts. Without proper incentive mechanism, local governments’ uncertain behavior following private partner’s sunk investment creates hold-up problems.

-

Risk mitigation: Introducing a third party (Platform) to Public-Private Partnership, which has the willingness and resources to induce adequate governmental efforts, will help alleviate the public-private distrust.

Note: This is an original piece by David Marx. Please cite according to Creative Commons 4.0 when sharing

Click here to download the PDF version

I. Introduction

Infrastructure is indispensable to socio-economic development. On the one hand, it reduces the cost of economic activities, such as energy, transportation, and communication, thereby promoting investment and industrial upgrading. On the other, it enhances people’s livelihoods, especially the poor, exemplified by the role of sewage facilities in the countryside 1.;

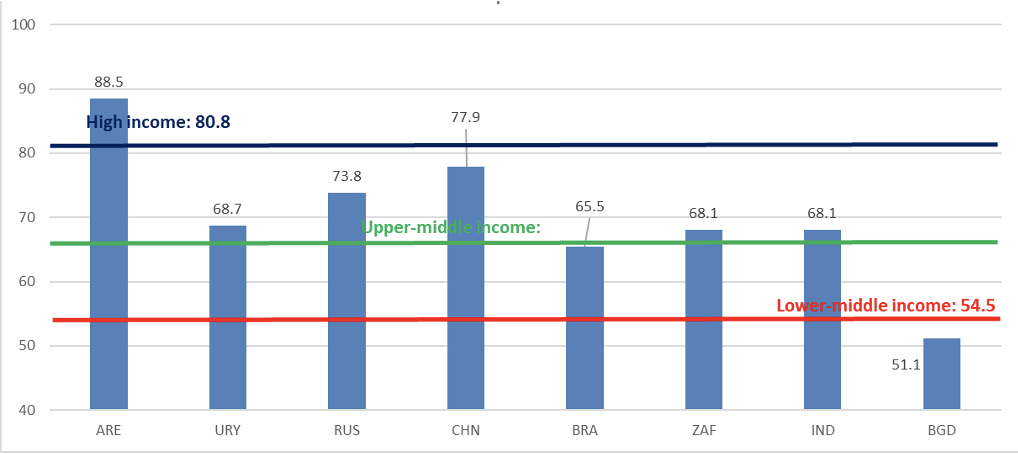

China has invested heavily in infrastructure in the past few years, but more is required for such a vast and populous country. According to the World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Index, China’s infrastructure competitiveness score for 2019 was 77.9, higher than the average for middle- and high-income economies (65.9) but still below the average for high-income economies (80.8). Meanwhile, infrastructure capital depreciates when heavily used and requires maintenance/upgrading.

Figure 1 World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Index 2019: Infrastructure

Figure 1 World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Index 2019: Infrastructure

However, infrastructure investment in China today faces new challenges. On the one hand, low-hanging projects (with high value and low cost) are now hard to find because of previous investment efforts and decelerating growth in urbanization and population. On the other, rising local government debt, together with those of financing vehicles, is limiting the role of the public sector in financing future infrastructure projects.

Therefore, it is necessary to invite more private participants to the construction and operation of infrastructure. This is something well observed by the national government. In April 2022, CPC’s Central Committee for Economic and Finance Affairs, Chaired by Xi, called for a modern infrastructure system and better implementation of the Public-Private Partnership (PPP) model.

To incentivize private efforts, the government must shift both earnings and risks of infrastructure projects to its private partners. However, as governments’ efforts are indispensable to the success of infrastructure projects, the government’s behavior following sunk investment, which is hard to document in complete and credible contracts, creates uncertainties for private partners. This leads to “investment hold-up” problems, in which private partners back out in infrastructure deals in fear of that governments, per its multiple social and economic objectives, threats to renegotiate after the private partners’ investments are sunk.

It requires a credible and enforcible judge for two teams to play a fair game. Introducing a third party with the willingness and resources to discipline the government can alleviate the hold-up problem. This third party, profiting from and dedicated to sustainable infrastructure development in the long run, act as a Platform, producing information, monitoring behavior, and enhancing the trust between the Public and the Private sector. In the late 1990s and 2000s, China Development Bank made such attempts in urban development projects. It leveraged its wholesale funding to require local governments in China to follow market-based rules and carry out their committements to infrastructure deals.

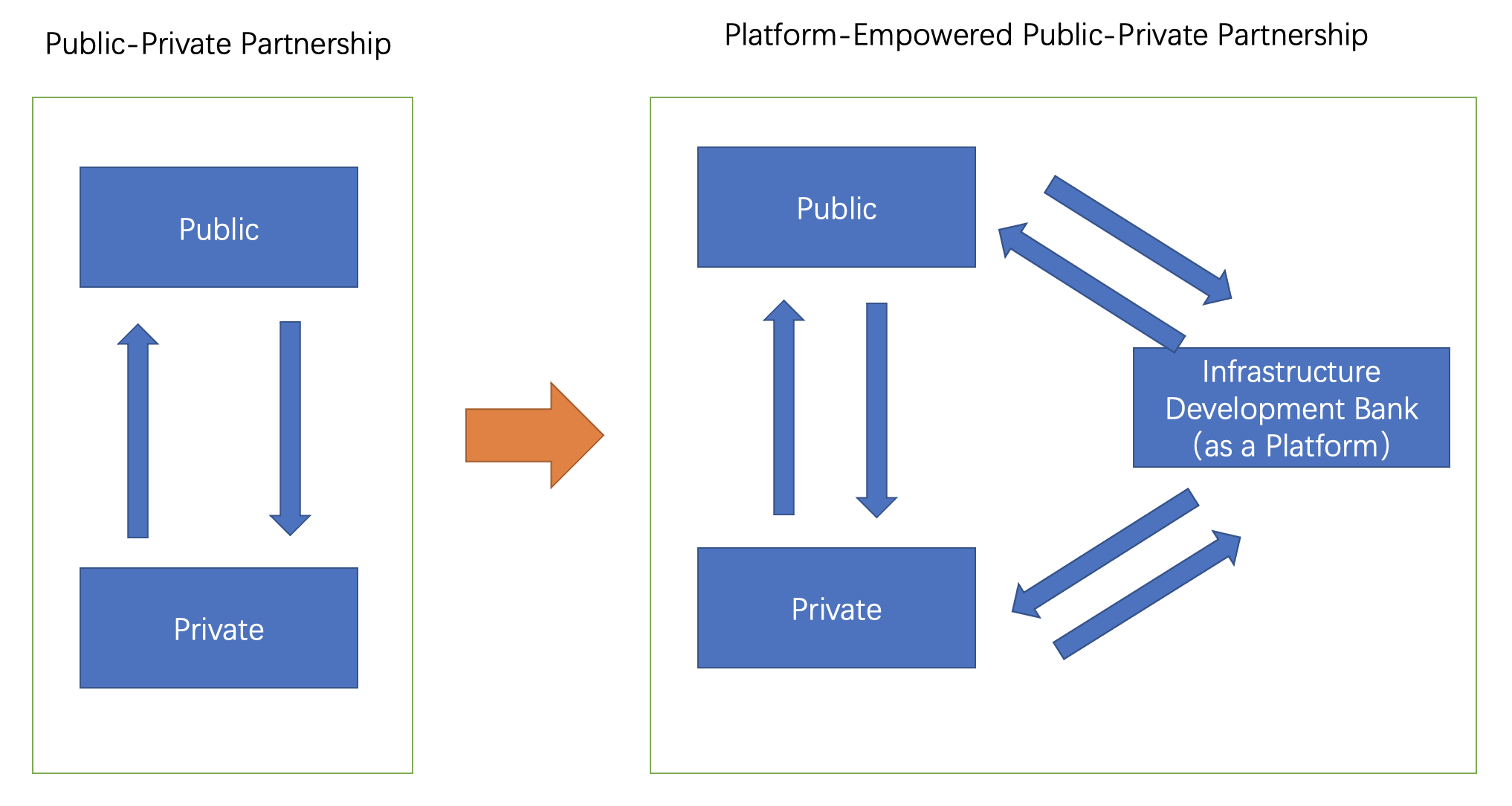

While PPP models shift risks, the Platform-Empowered PPP models mitigate risk, making infrastructure projects more attractive to private partners.

II. Risk Allocation in the traditional Public-Private Partnership models

Relying solely on governments for infrastructure services poses two problems. The first is insufficient investments: governments can only mobilize limited financial resources constrained by fiscal health; the second is inefficient investment and operation: governments lack the expertise to plan, build, and operate infrastructure projects, resulting in cost overrun, poor maintenance, and poor services. As a result, from the 1980s onwards, PPP models gained trends with variants such as BOO, BOT, BLO, etc., involving different capital contribution and repayment schemes.

When authorizing a private for-private partner to build or operate an infrastructure project, the government must also transfer risks associated with the project. Otherwise, moral hazard will arise as the private partner can bet on risk-taking behavior and wait for the government to bail it out when in trouble. From the perspective of fiscal health, PPP without adequate risk transfer is merely window-dressing balance sheets using off-sheet contingent liabilities (in the Chinese jargon, hidden government debt).

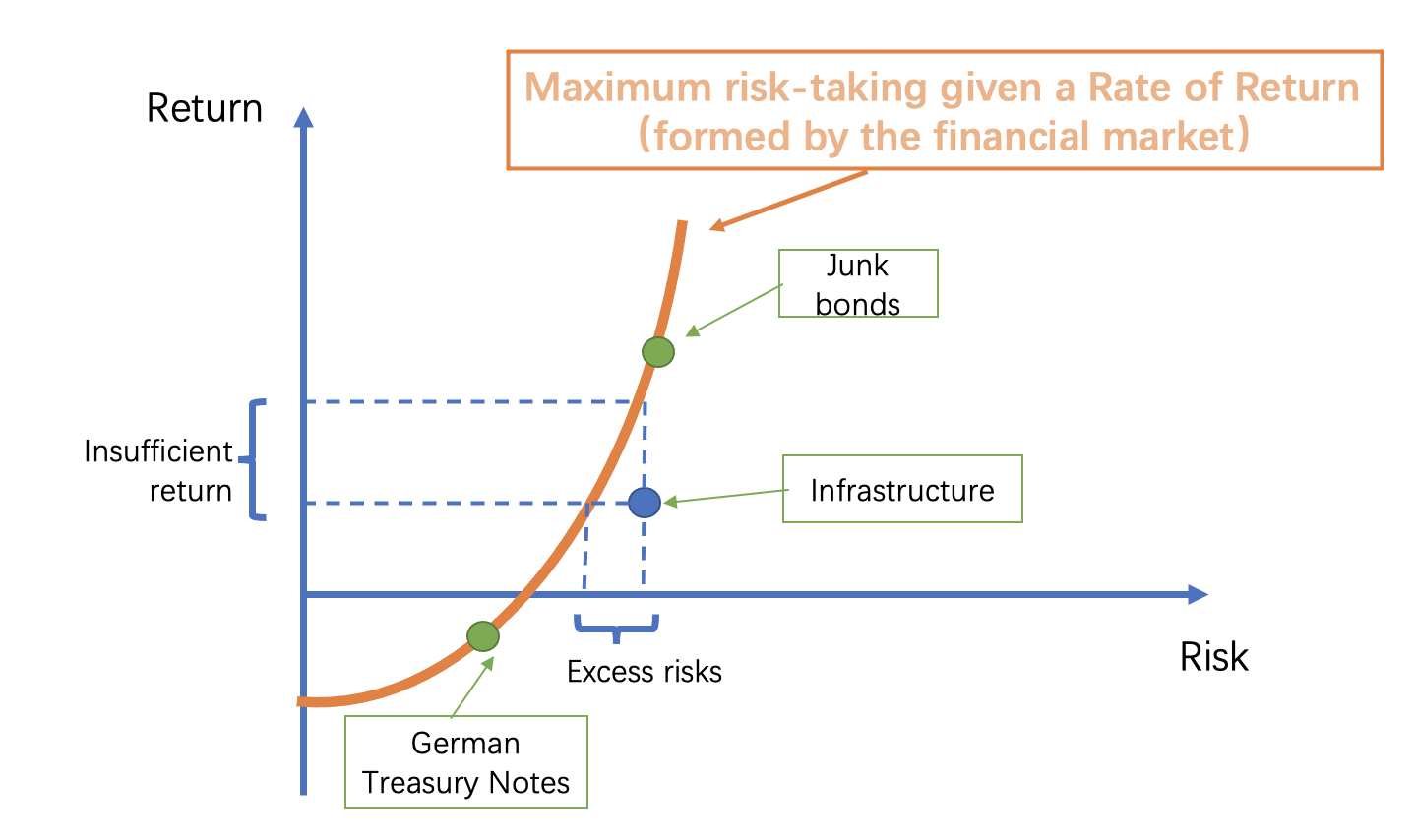

However, too much risk transfer drives out private investors. Many say infrastructure investment is not attractive to for-profit investors as the yields are low. This is only part of the story, as global investors held $13 trillion in negative-yield bonds in 2019 2. A more accurate statement is that, given its Rate of Return, the (perceived) risk of infrastructure projects is too high to be accepted by investors.

Figure 2 The Risk-Return Frontier

Figure 2 The Risk-Return Frontier

GIven high risks, investors will ask for higher yields as compensation (the logic of junk bond buyers), but this is usually not feasible for infrastructure projects. The reason is that these projects are public goods authorized by the government. Although economics agrees that high ex-ante risks can justify ex-post high returns, it is hard for society to accept infrastructure operators’ high profitability without demanding a lower service price. In addition, the high return may also lead to the government’s rent-seeking behavior and corruption.

Even if the high profitability is endorsed by the public and the government remains clean, there may not be enough investors willing to take high risks for high yields for infrastructure projects. All in all, according to S\&P, junk bonds (high-interest bonds) account for about 15% of all corporate bonds markets (2017) 3.

Therefore, risk mitigation should be prioritized when structuring PPP models.

III. Uncertain Government Behavior and Investment Hold-up

The construction and operation of infrastructure projects bear high risks because it involves the coordination of more parties over a longer compared with manufacturing projects, which are hard to avoid. For example, the COVID-19 has significantly cut the passenger flows of high-speed rails in the past three years, leading to negative operating profits and potential debt defaults. For another example, constructing subways in areas with large drifting stones requires experimenting with innovative engineering methods, the unforeseen difficulties of which may cause project delay and cost overrun 4.

However, besides those macroeconomic and engineering uncertainties, another kind of risk will arise after introducing a private partner to local infrastructure projects. In essence, the behavior of local governments affects the profitability of infrastructure projects significantly but is hard to fix due to contract incompleteness and unenforceability. Therefore, when the investment of private partners is sunk, local governments may, in pursuit of other socio-economic objectives, propose to renegotiate project terms by threatening to reduce their efforts in infrastructure projects. Foreseeing these risks, private partners either choose to ask for higher returns or back out from projects. This is the classic investment hold-up problem in economics.

3.1 Local governments’ efforts is indispensible for the success of infrastructure projects

Local government can alter the profitability of infrastructure projects through land collection, inter-governmental coordination, planning adjustment, and updated regulatory policies.

Land collection has always been a complex problem for infrastructure projects. Acquiring land is a gaming process involving many parties shaped by zoning and squitting policies. In areas without a formal land collection mechanism, the process easily forms a bottleneck for infrastructure projects. In an Asian Development Bank report, land collection was identified as the main challenge for Asian countries to invest in infrastructure and achieve industrialization 5. Brooking India also pointed out in a report that the government’s lack of experience and capacity in land collection poses a major obstacle to Infrastructure cooperation between India and South Asian countries 6.

Acquiring all necessary approvals from a list of government agencies may also be a headache. How many stamps does a project need to collect before launching? Land (or zoning), electricity, construction design, environment, water and sewage, fire safety, etc. Without synergy and coordination, the private partner may find it lengthy and burdensome (even desperate when finding out that two stamps are both the prerequisite of the others). In an interview, Mr. Zijian Cang, President of Vision Group, a key PPP participant in Beijing’s residential complex renovation projects, said that a multi-floor parking building complex requires approval from dozens of bureaus and the ‘green channel’ initiated by the government is critical 7.

The impact of planning and policy changes is even more pronounced. A new city council, with legislative approval, decided to focus more on the northern suburbs in the next ten years instead of the south, but how would those who invested in the subway lines in the southern suburbs in the past five years be compensated? A local government promised to collect pollution discharge fees and transfer them to the river cleaning firm as revenue in three years when the firm is operable, but what if legislative obstacles suddenly arise, forbidding discharge fees? Private partners, ten years ago, invested in a low-emission coal power plant with an expected life of 50 years. Is it okay to shorten its life to 20 years through legislation pursuing carbon neutrality?

These examples show that for the social capital of infrastructure projects, the actions of governments are influencial to the costs and benefits of infrastructure projects.

3.2 With complex objectives, the government may well choose to sacrifice the profits of infrastructure projects

But will government choose to make decisions deviating from the best interest of infrastructure projects? Unfortunately, in some situations, yes. The government has complex objectives, some of which may conflict with others in the short run. Therefore, in a public-private partnership where project risks are transferred to the private partner, the government may well choose to temporarily prioritize other objectives when investment is sunk.

For example, if the private partner makes enormous profits, the government may push for a lower infrastructure service price per public opinion. For example, the private partner invests in automated ticketing machines to reduce labor costs, while the government pushes for manual ticketing to sustain employment. Another case is that the government may, in economic downturns, incentivize counter-cyclical infrastructure investment by over-promising future payments, which harms existing PPP projects which depend on government payments (with higher fiscal future burden, payment delay or default becomes more probable).

3.3 Incomplete and unforcible contract leading towards investment hold-up

The government can and may be willing to sacrifice the profitability of infrastructure projects temporarily. Meanwhile, it isn’t easy to prevent this situation in complete and forcible contracts when entering PPP deals.

The incompleteness and unenforceability are a result of multiple factors. Firstly, government actions are hard to specify in contracts by setting up simple Key Performance Indicators. For instance, it is neither realistic nor legal for the government to promise to clear all approvals in 90 days no matter what. Secondly, governments’ actions are “invisible” or “unquantifiable” to outsiders, making it difficult to specify the “degree of effort” of the government in the contract. Thirdly, with strong public approvals and legislative efforts, the government can revise laws and regulations to support its policies. Finally, even if the contract is complete, the judicial process may be too long to endure for private investors. According to Arezki et al. (2017), infrastructure-related litigation against the government in India, a developing country with a well-established judicial system, often takes 3 to 10 years 8.

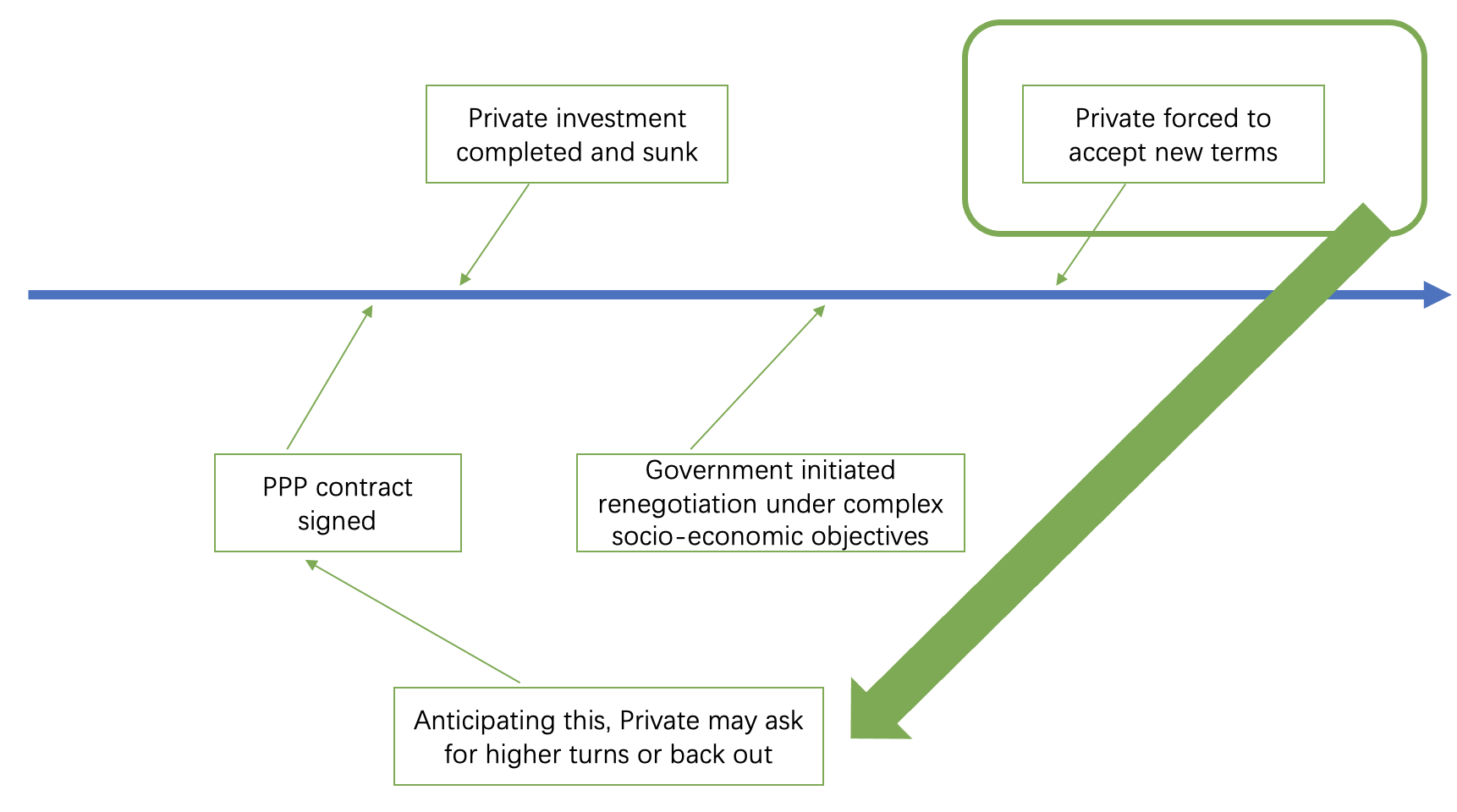

Therefore, for the private partner, once its investment is sunk, the government will be able to initiate renegotiation over contract terms. With a lower outside option, the private partner may have to choose between a low-profit scenario (the government makes little or no effort) and a negative-profit scenario (the government makes adverse efforts).

This is the classic “Investment Hold-up” problem in economics (see Grossman and Hart (1986 9) and Che & Sákovics (2018 10). When deciding whether to participate in infrastructure projects, potential private partners foresee the sequential gaming process, take into account the risks posed by the government, and choose either to demand higher yields or simply back out.

Figure 3 Sequencial Gaming of Investment Hold-up

Figure 3 Sequencial Gaming of Investment Hold-up

IV. Risk Mtigation by Introducing a thrid-party Platform

The investment hold-up problem results from unaligned incentives, incomplete and unenforceable contracts, and ineffective monitoring.

4.1 Lessons learnt from China’s Online Certified Product Platforms

This is similar to the trust crisis associated with China’s online shopping 20 years ago. At that time, the online shopping platform is merely an information provider, like BBS. Buyers were in fear of getting poor-quality products or being overcharged. Although sellers’ track records were displayed to all buyers, market volume remains low for two reasons. On the one hand, it takes time for new sellers to accumulate credibility. New sellers are hard to survive if everyone buys from those with good records. On the other, records cannot rule out sellers’ opportunistic behaviors such as buying good reviews. Goods with higher values saw lower trading volumes as customers were risk-averse.

Gradually, platforms started to run a new business called “platform-owned selling business”. In addition to the information provider, platforms acted as credit enhancers by promising the quality and authenticity of products. To fulfill the promise, platforms devoted efforts to verifying and supervising the products sold on the “platform-owned” sections, producing and channeling information from sellers’ side to buyers’ side as an independent third party.

Buyers are willing to trust platform promises because they are incentive-compatible. With even a small number of disputes, buyers will fly to competitors’ platforms, leading to a spiral of “lower customer-fewer sellers”. To ensure sellers comply with their rules, platforms established incentive mechanisms by linking product quality and customer satisfaction to trading fees and quality-assurance margins. Poor quality sellers may even be expelled.

4.2 Introducing a third-party platform to establish binding incentive mechanism to the government

Introducing an independent third-party platform to traditional PPP models can help alleviate the investment hold-up problem. Each nation (or state) can explore setting up one (or a few) infrastructure development bank(s) dedicated to the initiation, feasibility analysis, and monitoring of infrastructure projects. The bank enforces its disciplines by leveraging its funding and endorsement. For those who deviate from agreed-upon terms, the bank may limit the number of new projects in the following periods and warn private investors of the potential risks. In a sense, the development bank functions as an infrastructure platform binding both the public and the private.

To fulfill its platform responsibilities, an infrastructure development bank needs to possess at least the following characteristics.

Firstly, it has the expertise in structuring infrastructure projects to provide high-quality and objective consulting services in infrastructure planning, risk assessment, financial design, and project implementation.

Secondly, it has the resources and authority to motivate the government to behave in the interest of infrastructure projects.

Thirdly, answering to the national legislative authorities (such as independent central banks), it implements the national development strategy, promoting sustainable infrastructure development in the long run.

Fourthly, it operates under business sustainablity rule with strict reputation and financial risk control.

Figure 4 Platform-Empowered Public-Private Partnership

Figure 4 Platform-Empowered Public-Private Partnership

4.3 Historical referece: China Development Bank’s participation in urban construction projects practice in the late 1990s and early 2000s

In the 1990s, many Chinese cities faced significant infrastructure gaps, but the fiscal capacity of local governments was limited. Obtaining bank loans for infrastructure projects was also hard for two reasons. On the one hand, many existing projects, directly implemented by the government agencies, suffered from schedule delay and cost overrun. On the other hand, large banks were choked with substantial non-performing loans and were risk-averse.

It was against this situation that the China Development Bank (CDB) worked with the Chinese local governments to explore new project structuring and financing patterns, which strongly supported local infrastructure development while maintaining a relatively healthy risk profile.

CDB’s urban lending model around the 2000s had the following features. 11

First of all, it actively built its capacity in project analysis, engineering design, and long-term planning through cooperation with universities and international institutions, which helped filter projects and make valuable knowledge contributions to clients.

Second, leveraging its large-scale and cheap wholesale funding, the CDB talked Chinese local governments into acting per market-based rules. For instance, establishing independent urban construction firms to separate project funding accounts from governmental fiscal accounts, requiring that all agreed-upon future government payments be included in the annual budgets and endorsed by legislative authorities, and setting up joint working groups with local auditing offices to minimize corruption. In essence, the CDB linked the volume of loans to the behavior of Chinese local governments, which helped discipline their behavior when government officials are thirsty for development funding that few other institutions can offer.

Finally, as a development financial institution directly answers to the national government, CDB implemented the national strategy of developing infrastructure for the future with financial sustainability. It tried its best to help local governments structure projects to ensure financial viability. CDB regarded business sustainability as a hard constraint, strengthening the credit approval process with random and independent reviewing groups and a system in which no single person, the President included, can push a project through.

CDB’s case was cited in an important paper by Arezki et al. (2017 [8]). In this paper, five scholars, including the Nobel laureate J. Stiglitz, flagged information asymmetry and incentive mismatch in traditional PPP models and suggested that development banks (including multilateral development banks) could improve PPP models as a third party by acting as investment banks focusing on “Originate-to-Distribute (OTD)” models.

Although both emphasize the role of development banks, the Platform-Empowered PPP model is different from the OTD model in two aspects. First, the platform model addresses the investment hold-up problem resulting from uncertain government behavior when private investment is sunk and emphasizes incentivizing, monitoring, and disciplining government actions. Second, to better incentivize the platform to monitor government behavior continuously, it is incentive-compatible for the platform to borne a portion of risks in the project it endorses. Otherwise, it may not make the best effort in information production, as were investment banks and credit rating agencies before the 2008 global financial market.

-

For the impact of infrastructure on people’s livelihood in China, see “ZHANG Chi. Infrastructure Construction Contributes to Common Prosperity: China’s Experience [J].Journal of the Central Socialist Institute (in Chinese), 2021(06):82-92.” ↩

-

See https://investors-corner.bnpparibas-am.com/markets/chart-week-negative-debt/ ↩

-

See https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/pages/toc-primer/hyd-primer#sec5 ↩

-

This problem was encountered during the construction of Beijing Subway Line 9. See https://www.sohu.com/a/253845999_161623 ↩

-

Naoyuki Yoshino et al, 2018, LAND ACQUISITION AND INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT THROUGH LAND TRUST LAWS: A POLICY FRAMEWORK FOR ASIA, ADBI Working Paper Series. https://www.adb.org/publications/land-acquisition-and-infrastructure-development-through-land-trust-laws ↩

-

CONSTANTINO XAVIER and RIYA SINHA, 2020, When Land Comes in the Way: India’s Connectivity Infrastructure in Nepal, Brookings India. ↩

-

Beijing Youth Daily, Why is the “Jinsong Model” sustainable with small profits? “, https://view.inews.qq.com/a/20220105A00FAF00 ↩

-

Rabah Arezki, Patrick Bolton, Sanjay Peters, Frédéric Samama, Joseph Stiglitz, 2017, From global savings glut to financing infrastructure, Economic Policy, Volume 32, Issue 90, Pages 221– 261 ↩

-

Grossman S J, Hart O D. 1986. The Costs and Benefits of Ownership: A Theory of Vertical and Lateral Integration. Journal of Political Economy,94(4):691-719. ↩

-

Che Y, Sákovics J. 2018. Hold-Up Problem: The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics[Z]. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 5909-5915. ↩

-

See “CHEN Yuan, 2013, Aligning State and Market: China’s Approach to Development Finance, Foreign Language Press”. ↩