-

Sabotaging the economic hegemony of the British Empire: An America Dream in the 1930s

-

A Concealed Blade in the Helping Hand

-

Development Reaffirmed as a Top Priority

-

The Clash of Two Proposals

-

Plots inside the Mount Washington Hotel

-

Echoes of the History

Note: This is an original piece by David Marx. Please cite according to Creative Commons 4.0 when sharing

Click here to download the PDF version

The Bretton Woods Conference in July 1944 and the Bretton Woods system it formed are almost known to all who are interested in economics and international politics. However, how the agreements were reached, especially on the status of the US dollar equaling only to gold, was much less familiar even to trained economists.

I came across the book The Battle of Bretton Woods (Princeton University Press, 2014, henceforth BBW) recently, which offered a chance to take a close look at this topic. Written by Benn Steil, an American scholar trained in economies in Oxford, it fascinatingly describes the stories behind curtains, especially the financial confrontation between the British Empire and the United States during the interwar periods and the Second World War in detail, revealing a struggle with careful planning and calculation no easier than the Normandy landing.

Steil, Benn. 2014. The Battle of Bretton Woods. Princeton University Press.

In essence, it was a war without gun smoke launched by the United States, whose real economy just outperformed the British Empire, to break Britain’s financial and trade hegemony, and try to build a new international financial order most beneficial to itself. To this end, capable government bureaucrats of the US, represented by Harry White, devised careful and deep plots and attacked with precision, and finally beat the British gentleman, represented by John Maynard Keynes, to establish the US dollar hegemony, relying on strength, calculation, and deception.

This history of the Anglo-American struggle is rarely mentioned now, but it is thought-provoking enough to be remembered by contemporary policymakers.

Sabotaging the economic hegemony of the British Empire: An America Dream in the 1930s

The US enjoyed a prominent rise in the international scene following the end of World War I. It had already overtaken Britain as the world’s largest economy. It suffered no destruction during the devastating war, but was able to participate in the Paris Peace Conference as a victorious power, where other countries adopted its President’s advice to establish the League of Nations. The US, former colonies of the UK, seemed to be able to talk equally with other European countries on the future of the world.

However, behind those glorious moments, many Americans, especially the elites, were well aware that the US was not a dominant force in the international arena, and Britain, as a worldwide empire and the former “Boss” of the country, remains a nightmare.

Americans’ fear and hate of the UK during the Interwar Period was from a historical perspective. Just about 100 years ago, the British troops marched into Washington and burned the White House during the War of 1812. About 50 years ago, during the American Civil War, Britain, although ostensibly neutral, actually supported the Southern forces that supported cotton exports to the UK. Even with the War of Independence not mentioning, new grudge was constantly added to new hatreds between the US and the UK.

At the same time, although the United States had a strong military, its military capacity immediately deployable was not high compared to its European peers. In the 1930s, its Army of 174,000 soldiers ranked only nineteenth across the world, even behind Portugal. War Plan Red, the US military strategy approved in 1930 and updated in mid-1930s, envisioned a war with the British Empire, which would launch attacks from Canada, one of the Dominions of the Empire, and concluded that the US would only win the war after a hard struggle. Indeed, many of those areas now regarded as the backyard of the US were then part of the British Empire, and were frontlines that Uncle Sam would need to look after carefully.

Even from an economic point of view, the United States did not have the absolute dominant strength over the British Empire. In purchasing power parity (PPP) terms, the British Empire accounted for 19.7% of global GDP and 22.7% of the global population in 1913, while those of the US were 18.9% and 5.4% of the US, respectively.1 Although subsequently the US economy expanded faster, by 1938, America’s GDP in PPP terms was only 1.18 times that of the British Empire.2 For comparison, in 2022, China’s GDP in PPP terms was 1.19 times that of the United States,3 and the current Sino-US gaps in nominal GDP, finance, trade, science, and technology, as well as China’s insecurity to the US, may be applicable to the Anglo-America relationship back then.

Meanwhile, economic competition is so much more than overall production volumes and the real economy. The trade and financial hegemony of the British Empire was also intimidating to the US. The US suffered from Britain’s Imperial Preference policies, which reduced tariffs for British imports from its Colonies and Dominions, weakening the competitiveness of American products in the British market. Massive coverage of the Sterling Area, countries in which either use sterling for trade (mostly British Colonies, which stored sterling balances in London banks) or peg their currencies to sterling, caused substantial spillover effects for the US, i.e. when sterling devalues, the US exports became less competitive to those of the Sterling Area, while sterling appreciation forced the US to raise interest rate or to suffer from capital outflows.

The US had long wanted to sabotage the sterling area. For example, when China wanted to abandon the silver standard around 1935 China, it approached the US Treasury to purchase its silver reserves, which under the Silver Purchase Act of 1934 has large silver demand. One of the prices that the American side offered was for the Chinese currency to be pegged to the U.S. dollar, instead of the British pound.4

**In addition, the fact that London is a global financial center filled with speculative financial capitalists also annoyed the US. **As President Franklin Roosevelt (FDR) and his central economic adviser, then Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, dislikes bankers for their maneuvers over central banks and foreign exchange markets, sowing political turmoil.5 Morgenthau hated not only banks in London, but also those in New York, and claimed he would “move the financial center of the world from London and Wall Street to the United States Treasury and to create a new concept between the nations of international finance.”6

A Concealed Blade in the Helping Hand

Against the above background, it is not hard to understand that the American society was not on the British side to “fight for the democratic world” at the start of WW II. In 1939, less than 3% of Americans supported fighting along with the UK and France, while 30% were disapproving of trade with any countries in war.7 As for congressional constraints, legislation passed in previous years imposed an embargo on arms and other military materials and prohibited the US from extending credits to belligerents.

With intense efforts, FDR managed to push Congress to authorize arm sales to countries in war on a “cash-and-carry” basis, which required buyers to pay in gold or dollars and transport the goods with their own ships. For Britain, whose foreign exchange reserves were depleting soon, this was a bottle of water to a man in the desert, useful, but far from enough.

However, with the rapid advance of German forces, FDR and his advisers realized that short of American assistance, Britain’s defeat would be a matter of time, following which the US would face Germany’s naval threat alone in the east, in addition to that from Japan from the west. Therefore, FDR and Morgenthau began exploring possible ways to persuade Congress to do more.

This led to the famous Lend-Lease Agreement to the British’s recue. However, as the name shows, the US was not aiding the UK, rather, it only lent arms and civilian goods, demanding their return in physical or monetary forms, or other appropriate compensation upon the end of the war. The British side was well aware that, with war-destroyed production capacity, the Empire would have little for repayment, and would therefore rely on the mercy of the American side for their future, but had no better options. The US, on the other hand, proved to hold much less goodwill to the UK, because the technocrats of the Roosevelt administration, Morgenthau and White from the Treasury and Cordell Hull from the State Department, would cherish this opportunity to realize the American dream of weakening to the British Empire.

The Treasury colleagues tried their best to strategically delay the implementation of the Lend-Lease based on careful calculations, to reduce Britain’s foreign reserve to the minimum level possible and force the UK to fire-sell investments in the US. The fiber production firm American Viscose Corporation serves as a good example. It was one of the UK’s largest and most profitable assets in America but was forced to sell to American bankers at USD 54 million in 1941, half its market value.

The US State Department was less adamant on financial issues, not out of mercy, but because they eyed on the Imperial Preference system. Hull and his colleagues took the banner for free trade, despite their country being against it years ago, demanding the UK to end discriminatory trade policies, which was documented as Article VII of the Lend-Lease legislation, and made it clear that this was a “take it or leave it” issue. John Maynard Keynes, the father of Macroeconomics and a chief negotiator from the British side, called it “lunatic proposals”, while Churchill himself also tried to negotiate this with FDR several times. None of the efforts moved the American stances.

The Clash of Two Proposals

Both the US and the UK possess their own smart minds to carefully reflect upon the importance of post-war international monetary and financial arrangements even when victories were far from in sight. They were Harry White and John Maynard Keynes. They both realized that trade protection, competitive devaluation, and financial capital outflows were starters of international conflicts and that the world needed a multilateral monetary and financial architecture to sustain exchange rate stability, support international trade, and provide capital for post-war reconstruction, while an international organization must be established to attain the goals.8

Unfortunately, the above were almost all the consensus White and Keynes could share. To White, the interest of the US, the largest surplus country and gold reserve possessor lay in prohibiting other countries’ “hitchhikes”, either in the form of currency devaluation eroding the competitiveness of American products, or borrowing unlimitedly from the US or the newly established international organization to support irresponsible expansionary policies. For Keynes, his primary concern is to ensure Britain, as a country with little post-war production capacity or gold reserves but large debt and trade deficits, to maintain access to enough money or credits to meet imports while not being held under than gun barrel of the creditors.

With the above contrasting national interests in mind, White and Keynes drafted their own proposals.

White’s plan set gold and currencies backed by gold (namely the US dollar, for the US preserved two-thirds of global gold reserves at that time) as the new international reserve, with which countries would have settled international trade, effectively ending the international role of sterling. His plan also incorporated the establishment of a new international organization acting almost as a “world economic policeman” to monitor countries’ monetary policies and authorize countries’ requests to adjust exchange rates, which was the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Meanwhile, according to White’s plan, should structural trade imbalances emerge, deficit countries bear the sole responsibility for adjustment (through austerity policies), while surplus countries are not obliged to take any actions.

Keynes’s proposal, on the other hand, saw a much weaker status of gold, and argued to build the new international institution into a trade clearing bank. He empowered this institution to create a unit of account called Bancor, with which countries would settle international trade. Rather than linking to gold reserves, each country would receive a designated proportion of Bancor quota based on its volume share in international trade (both imports and exports count, obviously benefiting Britain). Keynes regarded monetary and exchange rate policies as sovereign decisions of any country, and thus should not require the authorization of supranational institutions. Also, in his plan, both deficits and surpluses of Bancor accounts would be constrained by limits, which means that, in addition to deficit countries, surplus countries would bear the responsibility for trade imbalance adjustment.

In the end, after rounds of negotiations, Britain made concessions and agreed to adopt White’s plan as the basis for international discussion. As for the reasons for the British compromise, it is said that the US Treasury hinted, or threatened, during the negotiations to suspend Lend-Lease on nonmilitary goods (i.e., requiring Britain to purchase civilian goods in gold or dollars).9 Obviously, this was not something the UK could afford during the intense fight against the Nazis.

Against this background, the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, participated by more than 700 delegates from 44 nations, was convened at the Mount Washington Hotel, in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, United States.

The game was finally on.

Plots inside the Mount Washington Hotel

Despite giving up Keynes’ plan, the British side still held wide disagreements with the US on various key issues on the future of the international monetary order. Are authorizations from the IMF needed for countries to adjust their exchange rates? How much financial resources can the IMF mobilize? What would be the status of the US dollar? During the preliminary negotiations between Britain and the US, Keynes pressed hard on those issues, but White shied away from making decisions, leaving most of the differences for discussions at the conference.

Keynes never believed that the 700-person conference would yield valuable breakthroughs, calling it “Monkey House”. What he didn’t know was that, in the eyes of the Americans, he was the exact monkey to be put on a show, to be kept busy under the spotlight, but far away from the key battles the US was about to fight.

First, he was asked to chair Commission II, the one which discussed the establishment of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, now the World Bank), where the UK and the US saw little disagreement. This occupied his mind and schedule, leaving no time for the discussion of international monetary arrangements and the IMF, which would be discussed in Commission I chaired by White.

Second, supporting staff of the conference, such as secretaries and assistants, were carefully selected by White from the Treasury Department and other government agencies, and of course, were all Americans. They were carefully trained to understand American interests, and were tasked to support all meetings for topic proposing, vote counting, minutes drafting, and the production of the final act to be signed by national representatives.10

Third, as advised by White, Morgenthau, in numerous bilateral discussions, leveraged the voting share of the IMF as a bargaining chip. It offered more voting power to them in exchange for their support on key issues in favor of the US.

Finally, White carefully set up the meeting procedures and controlled the flow of discussion. His team carefully supplied various alternative texts to existing drafts for meeting participants, hinting that some of them were jointly supported by the UK and the US, although many of the wordings were not confirmed by the British side. By taking control of the proceedings, White achieved an important goal, which is to “(a quote from Mr. White) prevent coming to a vote on matters which he doesn’t wish to come to a vote on, and in general arranging the discussion in such a way that we are never caught with an agreement among the Commission on something we don’t want, because then it is too late.”11

These arrangements paid off when White pushed for confirming the status of the US dollar in the post-war international monetary arrangement.12 Knowing that Keynes and the British side would never agree to appoint the US dollar as the sole fiat currency for international reserve, White avoided this issue in pre-conference bilateral negotiations with Keynes, with the draft act they discussed showing only gold would be used for international reserve.

However, through various meetings in Commission I which White chaired, he confirmed that most delegates would not read the documents carefully. He, therefore, instructed the American delegate, in a committee meeting of Commission I, to motion for revision of a piece of text on how the par value of an IMF member country’s currency should be expressed. Previously, the text reads “be expressed in terms of gold”, while the proposed Alternative A reads “be expressed in terms of gold, as a common denominator, or in terms of a gold-convertible currency unit of the weight and fineness in effect on July 1, 1944.” No one presenting at the meeting objected, and the revised text was passed from the committee meeting to the Commission 1 meeting.

As a second step, White delivered a long technical speech at a Commission I meeting, in which he deliberately mentioned the jargon “be expressed in terms of gold, as a common denominator, or in terms of a gold-convertible currency unit of the weight and fineness in effect on July 1, 1944.”. As expected, delegates started to ask the meaning of “gold and gold convertible exchange”. What was not expected was that the British delegate participating in the meeting, which was not Keynes because he was busy chairing meetings of Commission II, offered a technical explanation he supposed only on bookkeeping only the par value of a country’s currency, that “payment of official gold subscription should be expressed as official holdings of gold and United States dollars.”

Edward Bernstein, another American delegate who presented the meeting, soon concurred with the British explanation by saying that “it would be easier for this purpose to regard the United States dollar as what was intended when we speak of gold convertible exchange.” Seeing no objections, White quickly concluded this discussion and moved on to other issues.

The third step is much easier than the previous two. That night, White led his colleagues in the Drafting Committee to work up until 3 am, revising the 96-page final agreement texts, replacing all the term “gold” with “gold and US dollar”. White did not submit this revision for the review of Commission I delegates as if he only fixed some typos. In the end, this revised version was what was signed by the representatives of the 44 nations.

Mission Accomplished!

Yes, Keynes did not have enough time to read through the full text when he signed the agreement. According to him, the texts of the agreement were drafted behind the scenes by White and his team, and he received the full draft agreement and was asked to sign it at the last minute. In the end, Keynes did not find himself signing a document endorsing the US dollar’s international status until he left the United States.13

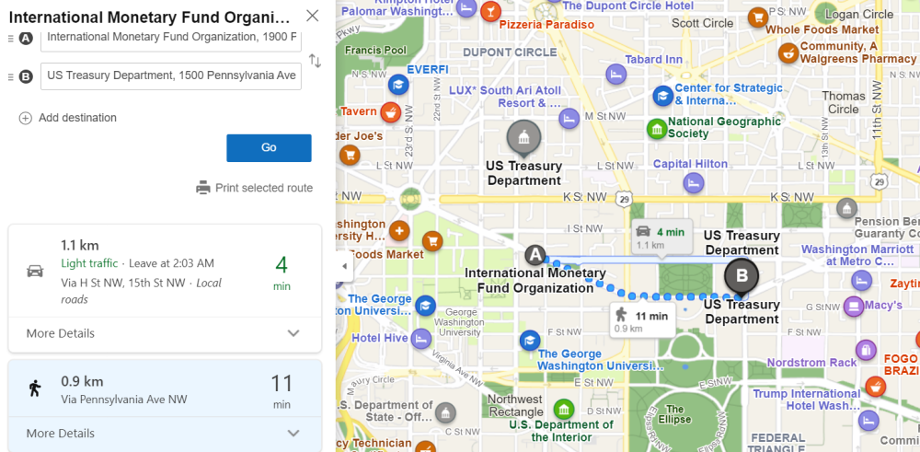

The location of the IMF and IBRD headquarters was hotly debated. The UK clearly wanted to locate both institutions in London, or at least adopt a two-headquarters arrangement in London and New York. The US would not yield and worked with other nations to ensure that both agencies were headquartered in the United States. Interestingly, the Bretton Woods agreement did not explicitly mention which US city would hold the headquarters. The British side presumed that it must be New York. However, on the eve of the IMF’s first executive board meeting in 1946, Keynes was told that both institutions would be housed in Washington, away from the maneuvers of New York bankers, but only 1.1 kilometers away from the U.S. Treasury. The British side raised objections, but they managed to settle the issue by cooperating with other major shareholders.

Today, it is customary for the President of the World Bank to be an American and the Managing Director of the IMF to be a European. This was not of out the mercy of the US, but a political scandal of White. According to Steil, the heads of both agencies should have been Americans. For the IMF, the Truman administration had already decided to nominate White as its first managing director, for he was acknowledged as the founder of the Bretton Woods system. However, President Truman was informed by security agencies, upon White’s nomination, that he might have been involved in spying activities for the USSR. Continuing the nomination was definitely impossible, but replacing White with another US citizen was sure to lead to questions on what happened to White, revealing his potential spy involvement, which would be used as a political weapon for Truman’s competitors. The President, therefore, ceded the IMF Managing Director to the Europeans without offering reasons.14

Echoes of the History

Nearly eighty years later, the stories of the Bretton Woods have been forgotten by many and are hard to find in textbooks and papers in economics. It is worth mentioning that these were not the only failed UK attempts to negotiate with the US for better treatments in the 1940s. Before the end of World War II, the United States also forced Britain to accept the post-war international political and economic arrangements many times by threatening not to offer loans. On one such occasion, Churchill even asked FDR whether the US President wanted him to “beg like Fala”, which was FDR’s dog.15

Nonetheless, with the sterling crisis in 1947 and the outbreak of the Cold War, as well as the stepping down of Morgenthau, White, and other Treasury bureaucrats, the US rapidly adjusted its UK policy, prioritizing helping Western Europe to restore economic capacity and resist the penetration of Soviet forces, led by the US State Department. Then came the Marshall Plan, in which the US provided USD 13 billion of aid to 16 European countries in exchange for their adoption of market economy policies and opening markets to each other.

Britain benefited profoundly from the Marshall Plan but would learn not to even dream about reviving its Empire. During the Suez crisis, President Eisenhower, angry with Britain’s aggressiveness, instructed Treasury officials to reject Britain’s much-needed IMF loan, giving the UK its first taste of the power of dollar diplomacy after WW II.

Meanwhile, as the United States transformed from a surplus country to a deficit country in the 1960s, some of the IMF’s hard principles, especially those benefiting surplus countries, became annoying to the superpower. In 1970, Pierre-Paul Schweitzer, then the IMF Managing Director and a French national, suggested that the US should devalue the dollar or raise its interest rates to reduce the trade deficits. President Nixon and his treasury colleagues refused this proposal steadily, asking Japan and other surplus countries to appreciate their currencies.16 This was essentially what Keynes asked for at the Bretton Woods conference, rejected by White.

In 1971, Nixon closed the gold exchange window, violating the solemn commitment the US made in 1944, dismantling the Bretton Woods system, but preserving its veto power in the IMF, its housing of the IMF headquarters, and the hegemony of the dollars.

We are still living in the echoes of that history today.

Keynes’s parents were both Cambridge University alumni, and his economics insights were first cultivated by grandmaster economist Alfred Marshall, as Keynes’ father was a good student of Alfred. Keynes was a humorous and thoughtful speaker, the founder of macroeconomics, and an English aristocrat, In the negotiations, Keynes was eloquent, well-informed, logical, and snarky when attacking others.

Yet he was defeated by White, the son of a family of Lithuanian Jews coming to the US, possessing no comparable literature skills and economics contributions to Keynes. Even if history proves that White’s plan is not a panacea for the world economy, the national strength of the US and the plot devised carefully by White and his colleagues were more than enough to give Keynes’s Bancor plan no trials.

The change of the international economic system was not a rhetoric on paper, but a struggle without gunfire. History is not written with mouths, but feasts.

What happened at Bretton Woods was the climax of what the Americans have been planning for more than ten years. Morgenthau, White, and many of the Treasury’s technocrats had been calculating this for too long. They successfully influenced their President, leveraged public opinions and congressional isolationist sentiments to press their counterparts, carefully designed meeting procedures to control the pace of the international conference, and recruited good lawyers to hide their true intentions behind ambiguous legal texts, and then explain it in their way in a variety of ways. They almost did nothing wrong in the plot.

Personally, it is astonishing that, as the sole superpower at the end of WW II, the US still planned the Bretton Woods conference so carefully, allowing for no accidents and mistakes, all to sabotage the glory of the British Empire. This history should not be buried, and every challenger to the US dollar’s international status should better remember it.

Let me end with a quote from the US delegation meeting upon the end of the Bretton Woods: ““Now the advantage is ours here,” the Secretary (Morgenthau) declared, calling for an end to the dithering and hand-wringing, “and I personally think we should take it.” “If the advantage was theirs,” White added, “they would take it.””17

-

The British Empire in this calculation includes the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the Indian subcontinent, Myanmar, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Nepal, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Egypt, see De Keersmaeker (2017), Polarity, Balance of Power and International Relations Theory, p. 90, https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-42652-5. ↑ ↩

-

Calculated by Statista Research Department based on the Maddison data, see https://www.statista.com/statistics/1334182/wwii-pre-war-gdp/. ↑ ↩

-

Data from IMF World Economic Outlook Database (April 2023); ↑ ↩

-

See Chapter 6 The Best Laid Plans of White and Keynes, BBW. ↑ ↩

-

“Central to this idea would be to boost the authority of governments over the rootless, selfish financiers who, partly through their hold over the national central banks, wreaked havoc in the currency markets, disrupted trade, and sowed political conflict.” See Chapter 6 The Best-Laid Plans of White and Keynes, BBW. ↑ ↩

-

See Chapter 6 The Best-Laid Plans of White and Keynes, BBW. ↑ ↩

-

Unless noted otherwise, contents in this section are summarized from Chapter 5 “The Most Unsordid Act”, BBW ↑ ↩

-

Unless noted otherwise, contents in this section are summarized from Chapter 6 The Best Laid Plans of White and Keynes, BBW. ↑ ↩

-

“The reason is Lend-Lease. Britain could not sustain its war effort without it, and the American Treasury viewed a British commitment to postwar currency stability and nondiscriminatory trade as vital considerations for it. At the same time White and Morgenthau were prodding the British to sign on to the Joint Statement, they were also pushing for the elimination of nonmilitary American Lend-Lease aid. The aim was to keep British balances below $1 billion, which would tie Britain into a position of extended dependence.” See Chapter 7 Whitewash, BBW. ↑ ↩

-

“To ensure that the monkey houses did not get out of hand, all the secretaries and assistants would be White’s closest Treasury associates and handpicked others from the Federal Reserve, the State Department, and other U.S. government agencies. It was they, and not the foreigners, or even the American delegates, who would select the subjects for discussion, count the votes, and—critically—write the minutes of the meetings and the final act.” See Chapter 7 Whitewash, BBW. ↑ ↩

-

The following 5 paragraphs were based on Chapter 8 History is Made, Location 4044 to 4084 in the BBW Kindle Edition. ↑ ↩

-

“We, all of us, had to sign, of course, before we had had a chance of reading through a clean and consecutive copy of the document,” Keynes offered by way of explanation five months later. “All we had seen of it was the dotted line. Our only excuse,” he added, lifting some prose from Shakespeare, “is the knowledge that our hosts had made final arrangements to throw us out of the hotel, unhouselled, disappointed, unaneled, within a few hours.” Chapter 9 Begging Like Fala. ↑ ↩

-

“These had quite simply changed the course of history. In their absence, the tradition of a European heading the IMF and an American heading the World Bank would surely have been reversed—assuming the Americans would not have laid claim to both.” See Chapter 10 Out with the Old Order, In with the New, BBW. ↑ ↩

-

“What do you want me to do,” Churchill bawled at one point, “stand up and beg like Fala?” the president’s dog.”” See Chapter 9 Begging Like Fala, BBW. ↑ ↩

-

“Nixon’s Treasury Secretary John Connally, a self-proclaimed “bullyboy,” angrily rejected suggestions from IMF managing director Pierre-Paul Schweitzer that the United States raise interest rates or devalue the dollar, instead blaming Japan, the newest destination for speculative capital in the wake of the mark’s float, for its “controlled economy.”” See Chapter 11 Epilogue, BBW. ↑ ↩